Nearly a quarter of adults in the world do not have access to a basic bank account. Financial technology (FinTech) innovations, such as mobile money, are one way to bridge this gap. Examples include M-Pesa in Kenya, Oi Paggo in Brazil and TCASH in Indonesia. All provide individuals with cheaper, easier, faster and more efficient ways of storing and transferring value. These efforts contribute to bridging the financial exclusion gap.

We used the World Bank’s definition of financial inclusion, which is where:

individuals and businesses have access to useful and affordable financial products and services that meet their needs – transactions, payments, savings, credit and insurance – delivered in a responsible and sustainable way.

Few FinTech firms in the global south have been able to replicate the success of FinTech innovations to reduce financial exclusion. The question is: why? We explore this question in our research paper and provide some answers.

Join 175,000 people who subscribe to free evidence-based news.

Get newsletter

The Ghanaian FinTech ecosystem

As is true in other countries, Ghana’s FinTech ecosystem is a complex and dynamic environment with interdependencies between various actors.

Regulators such as the Bank of Ghana provide policy and regulatory direction for the financial sector.

Traditional financial institutions such as commercial banks offer financial services through digital and physical branches. They are also the custodians of electronic funds transacted on FinTech innovations.

Telecommunications companies (telcos) also play a critical role. They use their mobile network platforms to offer digital financial services, popularly referred to as mobile money.

For their part, FinTech firms develop digital financial services. In Ghana, there are over 30 unique FinTech services. They include Qwikloan, Zeepay, G-money, Slydepay, and eTranzact.

Then there are the agents – small enterprises, acting as “shadow bank branches” or “cash-in, cash-out” points – providing support for digital financial services.

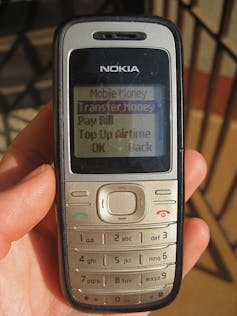

And, of course, the users that use FinTech innovations for financial transactions such as money transfer, securing micro-loans and paying bills.

Success factors

There is limited research about how new financial technology entrants and incumbents work together to shape financial inclusion. In our paper we try and bridge that gap.

We study the FinTech ecosystem in Ghana to learn how all the various actors work together to shape financial inclusion.

We did a case study with a range of organisations in Ghana. We identified three practices that are key to a well-functioning ecosystem for FinTech driven financial inclusion:

- innovative and collaborative practices

- protectionist and equitable practices, and

- legitimising and sustaining practices.

Innovative and collaborative practices: This involved substituting and refining established financial services and adopting new collaborative models to develop financial services.

We found that by refining and substituting established financial services through mobile money, many unbanked people were able to access financial services. This was because they didn’t need to visit bank branches, or provide strict documentation.

We also found that development and offering of FinTech innovations required unique collaborations. This was done through combination of technological capabilities, resources and relationships.

For instance, to offer microloan mobile money services, FinTech firms developed the mobile money applications, telcos offered the service through the mobile money platform while commercial banks acted as custodian of electronic funds.

This unique collaboration is new to the Ghanaian financial environment. It has led to many unbanked people being able to access financial services.

Protectionist and equitable practices: We found that the entrance of new actors triggered rivalry and new competition. Initially this stifled the growth of FinTech innovations in Ghana.

To address this impasse, the Bank of Ghana intervened with different policies such as the “E-money issuers” guidelines.

We find these policies to be both protectionist and equitable. They protected the interest of incumbents, like the banks. But they also ensured equity by recognising telcos and FinTech as ‘semi-autonomous’ financial institutions.

The introduction of the policies liberated the financial space and enabled rapid growth.

Legitimising and sustaining practices: These practices are symbolised by top-down revision of institutional arrangement and bottom-up trust building to create trust and sustain FinTech innovations.

We found that there was reorganisation at various levels. For instance, previously, FinTech firms were not legally recognised within the financial environment. But the Bank of Ghana introduced the Payment Systems and Services law (Act 987 of 2019) to legitimise their operations.

Similarly, we also found that the inclusion of mobile money agents enabled bottom up trust building and financial inclusion success.

Agents, as mediators between users and telcos, played a critical bridging role by offering direct access to services and support. Because agents live in communities they were able to build trust, and drive adoption.

We went on to explain how these practices shape financial inclusion. From this we propose theoretical propositions of how financial inclusion in developing countries is being scaled and shaped in terms of actors, relationships, and practices.

Big take-aways

Our study sheds light on the critical ingredients, but also suggests that more can be done to reduce financial exclusion further.

The big take-aways are that the development of FinTech services for financial inclusion requires pulling together capabilities between independent yet complementary competitors from three different traditional sectors. These are: information technology (for FinTech firms), telecommunication infrastructure and reach (for telcos) and banking (for banks).

We also lay out how regulations need to strike a balance between three competing interests: incumbents, new actors and citizens. Our findings suggest regulations that are both protectionist and equitable to incumbent and new actors can help balance the regulation of FinTech ecosystems.

Lastly, we set out how accounting for – and enabling – localised trust building can normalise practices to shape financial inclusion. We established the role of bottom-up trust building in the form of legitimising local mobile money agents and merchants to operate in the FinTech ecosystem.

This insight also explains why some FinTech initiatives from incumbents like branchless and mobile banking have not eliminated financial exclusion. Bottom-up trust building and building users’ trust is key to the successful use of FinTech services for financial inclusion.

From our work, it is evident that Ghana’s FinTech ecosystem practices are so far successful at reducing financial exclusion. But more can be done in terms of financial infrastructure expansion, literacy, elimination of transaction charges and developing solutions specifically for unbanked people.